Three levels of government: governing Australia

In Australia the three levels of government work together to provide us with the services we need. This in-depth paper explores the roles and responsibilities of each level, how they raise money and how they work together. Case studies show how the powers of the Australian Parliament have expanded.

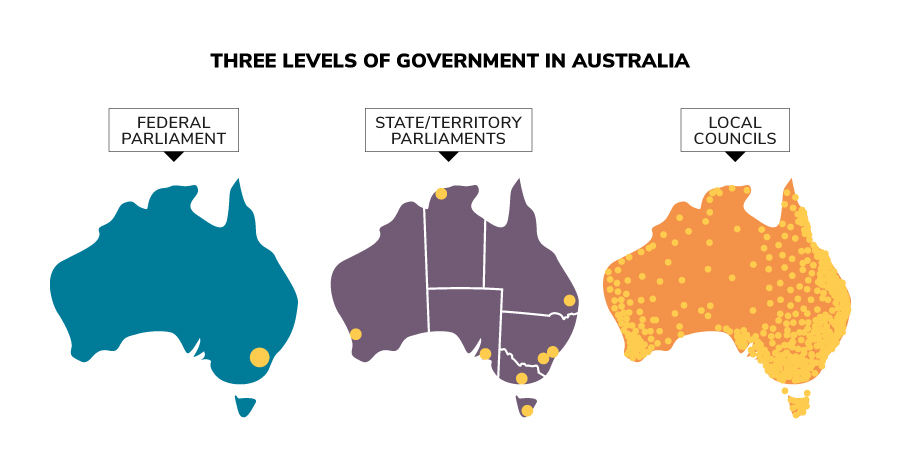

Three levels of government in Australia

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

The three levels of government – the law-making bodies in Australia. The Federal Parliament is located in Canberra, the nation's capital. State/territory parliaments are located in the capital cities of each of the 6 states and 2 territories. Local councils are located around Australia in each local council division.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

Australia has three levels of government that work together to provide us with the services we need:

- The federal Parliament makes laws for the whole of Australia.

- Six state and 2 territory parliaments make laws for their state or territory.

- Over 500 local councils make local laws (by-laws) for their region or district.

How the federal and state parliaments work together is sometimes referred to as the division of powers.

Each level of government has its own responsibilities, although in some cases these responsibilities are shared.

Australians aged 18 years and over vote to elect representatives to federal, state and territory parliaments, and local councils to make decisions on their behalf. This means Australians have someone to represent them at each level of government.

History

The establishment of the three levels of Australian government was an outcome of Federation in 1901, when the 6 British colonies – New South Wales, Western Australia, Queensland, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania – united to form the Commonwealth of Australia. Up until the 1850s each colony was run by a non-elected governor appointed by the British Parliament.

By 1860 all the colonies, apart from Western Australia, had been granted partial self-government by Britain (Western Australia became self-governing in 1890.) Each had its own written constitution, parliament and laws, although the British Parliament retained the power to make laws for the colonies and could over-rule laws passed by the colonial parliaments. By the end of the 19th century, many colonists felt a national government was needed to deal with issues such as defence, immigration and trade.

For Federation to happen, it was necessary to find a way to unite the colonies as a nation with a central or national government, while allowing the colonial parliaments to maintain their authority. The Australian Constitution, which sets out the legal framework by which Australia is governed, resolved this issue by giving Australia a federal system of government. This means power is shared between the federal – Australian – government and state governments.

Under the Constitution the states kept their own parliaments and most of their existing powers but the federal Parliament was given responsibility for areas that affected the whole nation. State parliaments in turn gave local councils the task of looking after the particular needs of their local communities.

Making laws

Federal Parliament

The Constitution established a federal Parliament. The 226 members of the Australian Parliament – 76 in the Senate and 150 in the House of Representatives – are responsible for making federal laws.

Sections 51 and 52 of the Constitution describe the law-making powers of the federal Parliament. Section 51 lists 39 areas over which the federal Parliament has legislative (law-making) power. These include:

- international and Australian trade and commerce

- defence

- postal and telecommunications services

- banking and insurance

- foreign policy

- citizenship

- taxation

- pensions

- census and statistics

- welfare payments

- currency

- Medicare

- national employment conditions

- marriage and divorce

- immigration

Under section 51 of the Constitution, state parliaments can refer matters to the federal Parliament. That is, they can ask the federal Parliament to make laws about an issue that is otherwise a state responsibility. Any federal law then made about the issue only applies in the state or states who referred the matter to federal Parliament or who decide to adopt the law.

Some of the powers listed in section 51 are exclusive powers of the federal Parliament. That is, only the federal Parliament can make laws in these areas. Some powers are shared with the state and territory parliaments. These powers are said to be concurrent. Exclusive powers of the federal Parliament are also included in sections 52, 86, 90, 114, 115 and 122.

Examples of exclusive and concurrent powers

EXCLUSIVE POWERSof the federal Parliament |

CONCURRENT POWERSpowers shared by the federal Parliament, and the state and territory parliaments |

|

Section 51

Section 52

Sections 86 and 90

Sections 114 and 115

Section 122

|

Education

Environment

Health

Marriage and divorce

Overseas trade

Taxation

|

Because the federal Parliament and the state parliaments can make laws in the same areas, sometimes these laws conflict. Section 109 of the Constitution states that if the federal Parliament and a state parliament pass conflicting laws on the same subject, then the federal law overrides the state law or the part of the state law that is inconsistent with it.

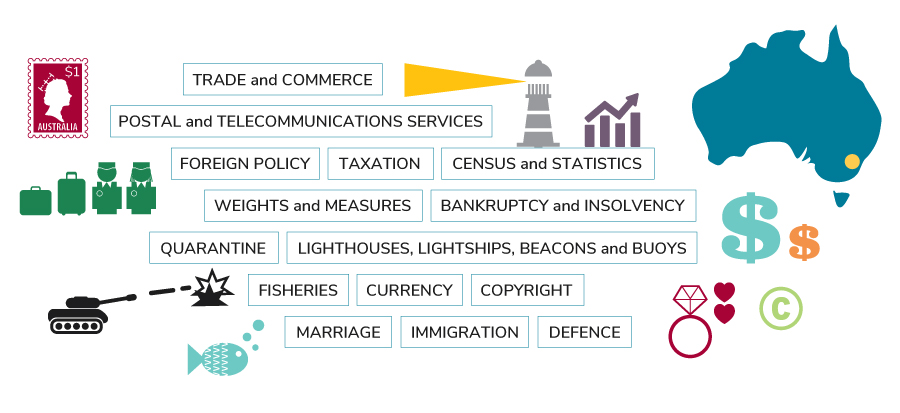

The law-making powers of the federal Parliament

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

The law-making powers of the federal Parliament include:

- trade and commerce

- postal and telecommunications services

- foreign policy

- taxation

- census and statistics

- weights and measures

- bankruptcy and insolvency

- quarantine

- lighthouses, lightships, beacons and buoys

- fisheries

- currency

- copyright

- marriage

- immigration

- defence.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

State and territory parliaments

Australia has 6 state parliaments. It also has 2 territory parliaments known as legislative assemblies. These parliaments are located in Australia's 8 capital cities.

Each state, apart from Queensland, has a parliament that consists of 2 houses. The Queensland Parliament has only one house – the Legislative Assembly – making it unicameral (single-house).

The Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory parliaments are also unicameral – both have one house called the Legislative Assembly. The Australian Capital Territory is unique in Australia because its parliament combines the responsibilities of both a local and state government.

Section 122 of the Constitution gives the federal Parliament the power to make laws for the territories. Until they were granted self-government, the Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory were administered – managed – by the federal government. Federal Parliament gave the territories self-government by passing the Northern Territory (Self-Government) Act 1978 and the Australian Capital Territory (Self-Government) Act 1988.

Other territories

There are 8 Australian territories in addition to the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) and Northern Territory (NT):

- Ashmore and Cartier Islands

- Australian Antarctic Territory

- Christmas Island

- Cocos (Keeling) Islands

- Coral Sea Islands

- Jervis Bay Territory

- Norfolk Island

- Territory of Heard Island and McDonald Islands

These territories are governed according to Australian – federal – law and the laws of a state, the ACT or NT. Most have an appointed Administrator.

State and territory parliaments make laws that are enforced within their state or territory. By defining federal powers, the Australian Constitution reserved – left – most other law-making powers to the states. These are called residual powers. As a rule, if it is not listed in sections 51 and 52 of the Constitution, it is an area of state responsibility. State laws relate to matters that are primarily of state interest such as:

- schools

- hospitals

- roads and railways

- public transport

- utilities such as electricity and water supply

- mining

- agriculture

- forests

- community services

- consumer affairs

- police

- prisons

- ambulance services

Section 122 of the Constitution allows the Parliament to override a territory law at any time. The federal Parliament has only used its power under section 122 a few times and only in cases where the territory law has created much debate or controversy within the Australian community.

Up until 2011 the self-government Acts covering the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory gave federal ministers the right to veto or change territory laws without approval of federal Parliament. This veto power was used by Prime Minister John Howard in 2006 to disallow the Australian Capital Territory's civil union laws. Federal Parliament has now amended the self-government Acts so the federal Parliament must vote to veto a territory law.

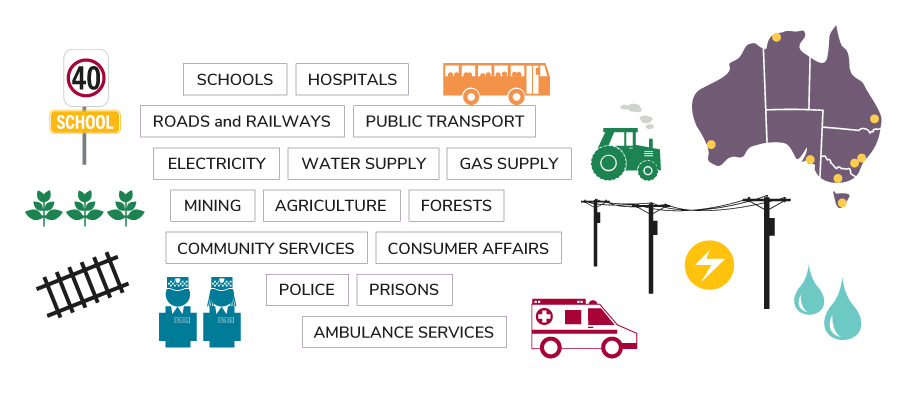

The law-making powers of state parliaments

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

The law-making powers of the state parliaments include:

- schools

- hospitals

- roads and railways

- public transport

- electricity

- water supply

- gas supply

- mining

- agriculture

- forests

- community services

- consumer affairs

- police

- prisons

- ambulance services.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

1997

In 1997 federal Parliament passed a law to overturn the Rights of the Terminally Ill Act 1995 (NT), which made euthanasia legal in the Northern Territory. The territory law allowed terminally ill patients to decide when to die. After a free vote the federal Parliament passed the Euthanasia Laws Act 1997. As a result of this law, the self-government Acts of the territories were changed to stop the territory parliaments making laws about euthanasia.

Councils

There are over 500 local government bodies across Australia. They are often called councils, municipalities or shires. Local governments consist of 2 groups who serve the needs of local communities:

- Elected members, who normally have 4-year terms.

- Staff who work for the council.

On average each council has 9 elected members who are usually called councillors or aldermen, while the chair or head of the council is usually called the mayor or president. These smaller legislative bodies make by-laws about local matters and provide services. For example, councils are responsible for:

- local roads, footpaths, cycle ways, street signage and lighting

- waste management, including rubbish collection and recycling

- parking

- recreational facilities such as parks, sports fields and swimming pools

- cultural facilities, including libraries, art galleries and museums

- services such as childcare and aged care

- sewerage

- town planning

- building approvals and inspections

- land and coast care programs

- pet control.

One of the main tasks of local government is to regulate – manage – services and activities. For example, councils are responsible for traffic lights, and dog and cat registration. These tasks would be difficult for a state government to manage because they are local issues.

Councils can deliver services adapted to the needs of the community they serve. For instance, the needs of residents in inner-city Brisbane might be different to those of people living in rural Queensland. By providing these services and facilities, councils make sure local communities work well from day-to-day.

From the 1840s colonial parliaments began to hand over responsibility for local issues to local councils. The first council was established in Adelaide in 1840, followed in 1842 by the City of Sydney and Town of Melbourne councils. From the 1850s onwards, the number of elected councils grew rapidly.

Today, local authorities include city councils in urban centres, and regional and shire councils in rural areas. On average each council looks after about 28,400 people. The largest council by population is Brisbane City Council which is responsible for a population of nearly 1.2 million. The Shire of East Pilbara in Western Australia is the largest local authority area.

Local councils are not mentioned in the Australian Constitution, although each state has a local government Act – law – that provides the rules for the creation and operation of councils.

While these Acts vary from state to state, in general they cover how councils are elected and their power to make and enforce local laws, known as by-laws. A by-law is a form of delegated legislation because the state government delegates – gives – to councils the authority to make laws on specific matters. As councils derive their powers from state parliaments, council by-laws may be overruled by state laws.

The law-making powers of local government

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

The law-making powers of local governments include:

- local roads, footpaths, cycle ways, street signage and lighting

- rubbish collection and recycling

- parking

- parks, sports fields and swimming pools

- libraries, art galleries and museums

- childcare and aged care

- sewerage

- town planning

- building approvals and inspections

- land and coast care programs

- pet control.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

Putting laws into action

Each of the three levels of government has its own executive that puts laws into action.

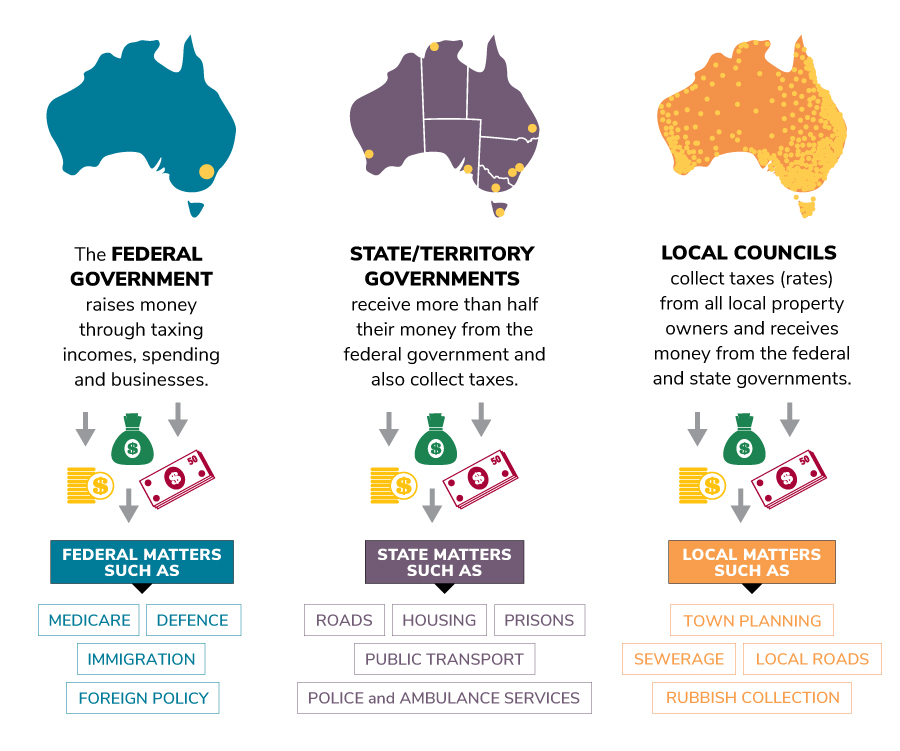

How governments in Australia raise and spend money

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

The federal government raises money through taxing incomes, spending and businesses. The money is spent on federal matters such as: Medicare, defence, immigration, foreign policy.

State/territory governments receive more than half their money from the federal government and also collect taxes. The money is spent on state matters such as: roads, housing, prisons, public transport, police and ambulance services.

Local councils collect taxes (rates) from all local property owners and receives money from the federal and state governments. The money is spent on local matters such as: town planning, sewerage, local roads and rubbish collection.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

Federal executive government

The federal executive – the Prime Minister and ministers – is the main decision-making body of the Australian Government and is responsible for putting federal laws into action. It also makes sure laws provide Australians with the services they need.

If a minister needs to introduce a new law or change an existing one, they must first get the approval of the federal executive. The minister then works with their government department to prepare the bill – proposed law – before it is considered by the Parliament.

The executive government needs money to put laws into action. It raises money by collecting taxes on incomes and company profits, and through other charges such as fuel excise and customs duties.

| Federal | State and territory | Local |

| The federal government raises money to run the country by collecting taxes on incomes, goods and services, and company profits, and spends it on national matters: for example, trade, defence and immigration. | State and territory governments also raise money from taxes but receive more than half their money from the federal government and spend it on state and territory matters: for example, schools, housing, hospitals, roads and railways, police and ambulance services. | Local councils collect taxes – rates – from all local property owners and receive grants from federal, state and territory governments, and spend this on local matters: for example, town planning, rubbish collection, water and sewerage, local roads and pet control. |

Once a year the Treasurer delivers the Budget to Parliament, which explains how the government will raise and spend this money. The government must gain approval for its Budget from Parliament. It does this by asking Parliament to pass a series of bills called Appropriation Bills.

Ministers manage the share of the Budget that has been given to the department they are responsible for. They use this money to administer the laws and programs that fall within their portfolio. The executive government also gives revenue – money – collected through the tax on goods and services (GST) to the states and territories to help fund their delivery of services.

State and territory executives

States and territories also have executive governments. There are 6 state and 2 territory executive governments. State executive governments are made up of a premier and state ministers. Territory executive governments are made up of a chief minister and territory ministers. These ministers are elected members of the state or territory parliament, and come from the party or coalition of parties that forms government in the lower house. State and territory executives decide on policy and new laws, including how to put state or territory laws into action.

State and territory executive governments get about half their money, including their share of the goods and services tax (GST), from the federal executive government. They also raise money from taxes and charges such as:

- stamp duty – a tax on legal documents

- payroll tax – a tax on the total amount of salaries paid by an employer

- motor vehicle registration

- land tax – a tax paid by certain land owners on the unimproved value of their property, including holiday homes, investment properties and vacant land

- gambling licenses.

The states and territories spend this money to manage laws and to provide goods and services to the people of their state or territory. State and territory ministers, like federal ministers, manage the budget given to the government department they are responsible for.

The local executive

Elected councillors decide on policy and make by-laws for their community at council meetings. These decisions are then administered – put in place – by the chief executive officer and other non-elected employees of the council.

Local governments receive part of their income in grants from federal, state and territory executive governments. Councils also raise their own money from local taxes such as rates – tax on the value of property – sewerage and water charges, dog licences and user fees for sporting facilities and libraries.

Changes in the federal and state relationship

Since Federation some rulings made by the High Court of Australia have strengthened the law-making powers of the federal Parliament. The High Court can resolve disagreements between the federal and state governments over their law-making powers. If a law is contested – challenged – it is up to the High Court to determine whether the Constitution gives the relevant parliament the power to make this law. A law judged by the High Court to be unconstitutional is then invalid, meaning it is over-ruled.

The states' reliance on federal government funding to pay for activities such as schools and hospitals has also shifted the federal-state balance. Federal funding grants make up about half of the states' total revenue. Under section 96 of the Constitution, the federal Parliament can 'grant financial assistance to any State on such terms and conditions as Parliament thinks fit'. This allows the federal government to give 'tied' grants to state governments, directing the state government on how to spend the money. The federal government can then influence the way things are done in areas such as education, health, housing and transport, which are primarily state responsibilities.

The law-making powers of the federal Parliament have also grown to deal with the huge social and technological advances that have occurred since Federation. As Australian society has changed, so too have the issues facing federal Parliament. For instance, the drafters of the Constitution could not have foreseen how the digital revolution has impacted the way we live, work and communicate. In 1901 there were only 33,000 telephones in Australia and no radio, television, computers or internet. Today the federal Parliament makes laws about all of these services. It is able to do this under section 51(v) of the Constitution, which gives Parliament responsibility for 'postal, telegraphic, telephonic and other like services'.

Cooperation

Members of the federal, state and local executives are required to work together in order to solve complex problems.

The National Cabinet, which includes the Prime Minister, premiers, and chief ministers, meets regularly to discuss intergovernmental matters.

Ministers from the various levels of government also work together on matters of common concern. For example, the Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council meets regularly to negotiate a coordinated national approach to health policy.

As a result of intergovernmental discussions, uniform national laws have been made to tackle issues such as road transport, food standards and consumer rights. By introducing uniform national laws, the three levels of government can operate together with a greater level of efficiency.

Case study 1

Radio Licence Case 1935

Until 1974 the federal government charged households a fee, or listener's licence, for each radio set they owned. The fees were used to pay for radio stations. In 1934 Dulcie Williams from Surry Hills in Sydney refused to pay the listener's licence on the grounds wireless radio is not mentioned in the Constitution. In doing so she challenged the federal Parliament's right to make laws about broadcasting.

The case went to the High Court, who found in favour of the government based on section 51(v) of the Constitution. This section gives federal Parliament responsibility for 'postal, telegraphic, telephonic and other like services'. The Court decided wireless radio could be defined as being like a telegraphic or telephonic service because it involved sending communications.

The High Court's interpretation of section 51(v) means that today the federal Parliament can make laws about all forms of communication, including television and the internet. For example, it has passed laws to regulate the use of the internet, tackle cyber crime and invest in infrastructure such as the National Broadband Network.

Case study 2

Tasmanian Dam Case 1983

In 1978 the state-owned Tasmanian Hydro-Electric Commission announced plans to dam the Franklin River and flood a large wilderness area in south-west Tasmania. Four years later the area was declared a World Heritage site under the World Heritage Convention, to which the federal government is a signatory – Australia has agreed to the convention.

The federal Parliament then passed laws to stop clearing and excavation within the newly listed Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage area. The Tasmanian government challenged the laws in the High Court of Australia, arguing the federal Parliament did not have the power to stop the construction of the dam.

In 1983 the High Court ruled that, under its external affairs power, the federal Parliament could make laws relating to international treaties which Australia had signed. The external affairs power, listed in section 51(xxix) of the Constitution, allows the federal Parliament to enter into international treaties and agreements on behalf of Australia.

Although the federal Parliament has no law-making powers over Tasmania's rivers, dams or environment, the court decided the federal legislation was valid because it allowed the government to meet its commitments under an international treaty – the World Heritage Convention.

When the Constitution was written, treaties mainly related to peace and trade but today they also deal with matters that are defined as state responsibilities – for example, human rights, environmental protection and discrimination. As a result of the High Court ruling, the federal government can now make laws in these and other areas in order to honour treaty agreements.

Case study 3

The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park

In the 1960s and 1970s the Queensland Government sought to commercialise the natural resources of the Great Barrier Reef. In response, the growing environmental movement organised protests against the expansion of mining and oil drilling in this sensitive environment.

In 1969 the federal and Queensland governments jointly established an inquiry into the ‘possibility’ of oil drilling causing damage to the reef. This inquiry was upgraded to the federal Royal Commission into Exploratory and Production Drilling for Petroleum in the Area of the Great Barrier Reef, which recommended the creation of a marine park to protect the Reef.

In response the federal and Queensland governments agreed to ban oil drilling in the territorial waters they controlled and the federal Parliament passed the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Act 1975. This created a federal agency to grow and administer the new park in conjunction with the Queensland Government.

The Queensland Government manages the day-to-day operations of the Park, including undertaking state responsibilities such as issuing fishing and tourism operator licenses. The federal and Queensland governments work with local councils along the Queensland coast to protect and preserve the marine park. For example, local councils are responsible for stormwater treatment, ensuring water running into the reef is free from pollutants.

From policy to law

Parliamentary Education Office (peo.gov.au)

Description

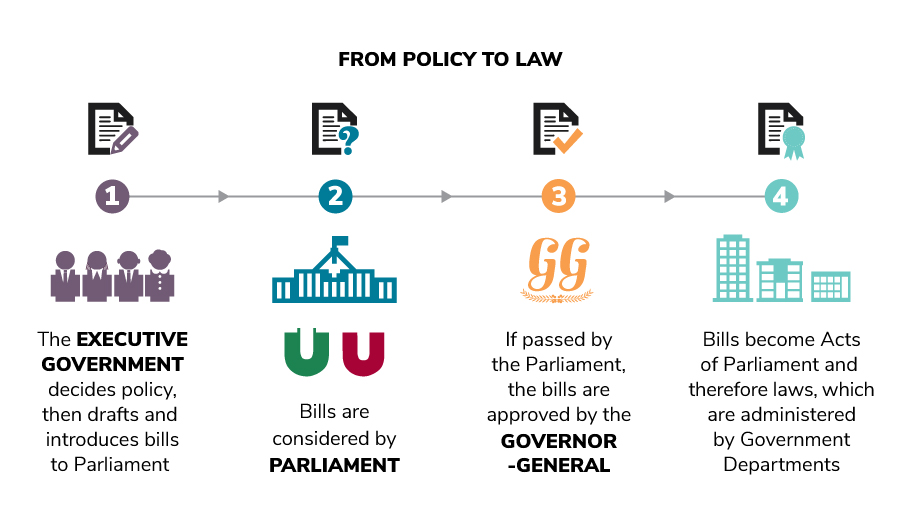

The role of executive government in turning policy into law:

1. The executive government decides policy then drafts and introduces bills to the Parliament.

2. Bills are considered by Parliament (in the House of Representatives and the Senate).

3. If passed by Parliament, the bills are approved by the Governor-General.

4. Bills become Acts of Parliament and therefore laws, which are administered by government departments.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.