Parliament and the courts

This fact sheet outlines the relationship between the Australian Parliament and federal courts, including the separation of powers and key High Court of Australia cases that have impacted the powers of the Australian Parliament.

What will I learn?

- The Parliament and Judiciary work independently of each other.

- Parliament makes law and the Judiciary makes judgements about the law.

- High Court decisions can sometimes limit, expand or confirm Parliament’s power to make laws in specific areas.

Curriculum alignment

Year 8 ACHCK063

Year 9 ACHCK077

Year 10 ACHCK092

What power do Parliament and courts have?

In Australia, the power to make and manage law is divided between the Australian Parliament, the Executive – the Australian Government – and the Judiciary – the courts. This division is based on the principle of the 'separation of powers' and is outlined in the Australian Constitution:

- The Australian Parliament has the power to make laws for all Australians.

- The Judiciary – the High Court of Australia and other federal courts – has the power to interpret laws made by Parliament and judge if laws are consistent – valid – with the Constitution.

- The Executive come up with ideas for new laws or changes to existing laws and are responsible for putting laws into action.

The relationship between Parliament and the courts

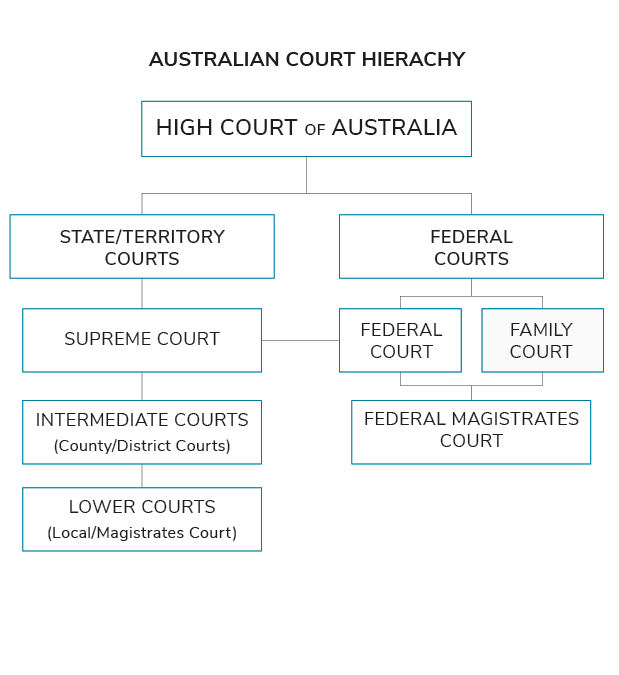

Court hierarchy

Parliamentary Education Office

Description

The High Court of Australia sits at the top of the court hierarchy. Underneath this court are:

- State/territory courts

- Supreme court

- Intermediate courts (county/district courts)

- Lower courts (local/magistrates court)

- Federal courts

- Federal court/family court

- Federal magistrates court.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

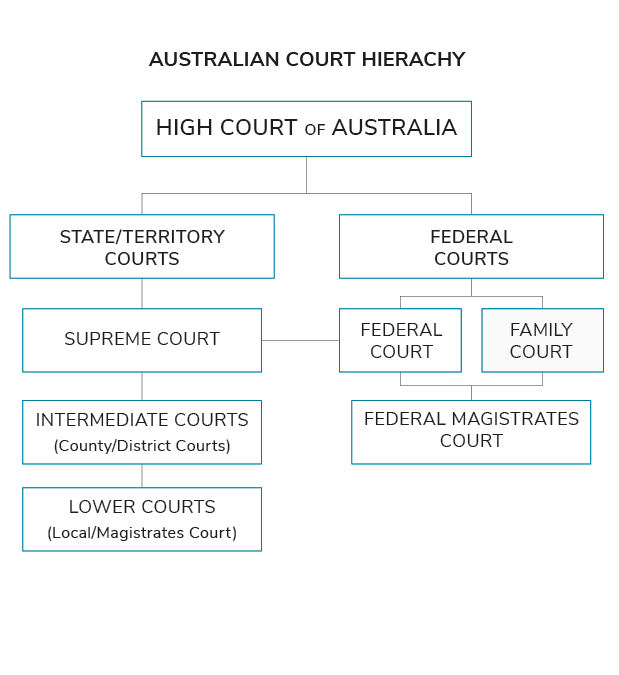

Court hierarchy

Parliamentary Education Office

Description

The High Court of Australia sits at the top of the court hierarchy. Underneath this court are:

- State/territory courts

- Supreme court

- Intermediate courts (county/district courts)

- Lower courts (local/magistrates court)

- Federal courts

- Federal court/family court

- Federal magistrates court.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

You are free to share – to copy, distribute and transmit the work.

Attribution – you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author or licensor (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work).

Non-commercial – you may not use this work for commercial purposes.

No derivative works – you may not alter, transform, or build upon this work.

Waiver – any of the above conditions can be waived if you get permission from the copyright holder.

Parliament and the courts are independent of each other. For example:

- The Parliament can only create law; it cannot judge if the law has been broken.

- The Australian Parliament has the right to make, change or repeal – remove – any law within the limits of the Constitution. Courts cannot challenge or remove this right of the Australian Parliament.

- The power of the High Court cannot be changed by a decision of the Parliament.

- Parliament does not have the power to remove judges if they are unhappy with their decisions.

- The salary of High Court judges cannot be reduced by Parliament.

However, they are not completely separate; for example:

- The Australian Parliament can make laws which create Federal courts.

- The High Court can judge that a law made by the Parliament was inconsistent with the Australian Constitution and invalidate it – cancel it.

The decisions of judges, which act as binding precedents for later decisions, are known as common law. However, statute law – laws made by Parliament – overrides common law. This is called parliamentary supremacy.

Influence on laws

The Parliament, Judiciary and Executive each contribute to the way laws are managed in Australia:

| Parliament | Judiciary | Executive |

| Makes and changes statute law – legislation | Makes and changes common law | Introduces ideas for statute law into Parliament |

| In some circumstances, gives law-making power to the Executive and government officials – delegated legislation | Interprets law and provides precedent to the way it will apply in certain cases (statutory interpretation) | Can be given law-making power by Parliament |

| Can create law which overrides common law – abrogation | The High Court decides whether a law is consistent with the Australian Constitution | Runs government departments that put laws into action |

High Court cases

The High Court of Australia

DPS Auspic

Description

The High Court of Australia in session in the High Court building in Canberra. The High Court interprets and applies Australian law and decides cases about national issues, including challenges related to the Australian Constitution.

In the courtroom, the 7 High Court Justices sit along a large semi-circular desk atop a small raise at the end of the room. The Justices preside over High Court proceedings, interpret laws and decide major legal cases.

In front, facing them, is another curved desk. Here, 18 barristers are sitting, most are wearing robes and wigs. A barrister is a type of lawyer who speaks on behalf of people or organisations in the courtroom. They present arguments and answer questions posed by the Justices.

Copyright information

Permission should be sought from DPS AUSPIC for third-party or commercial uses of this image. To contact DPS AUSPIC email: auspic@aph.gov.au or phone: 02 6277 3342.