The Federation of Australia

Australia's Federation came about through a process of deliberation, consultation and debate. This in-depth paper explores the reasons for Federation, the Federation conventions and the referendums in which the Australian people decided to join together as a nation.

"Combine Australia!"

Punch, National Museum of Australia. Photo: Dragi Markovic

Description

In the centre of a ring of kangaroos stands a lion wearing a green jacket and carrying a cricket bat. His cap is printed with a Union Jack. The kangaroos wear blue and white stiped jackets with a yellow waist band. They are printed with 'New South Wales', 'Queensland' and 'Victoria'. An umpire watches on. Printed at the bottom is: 'Combine Aust! Umpire Punch: "You've done jolly well by combination in cricket field, and now you're going to federate at home. Bravo, boys!"'

Sporting union predated federation. In 1877 an intercolonial cricket team represented Australia in the first test match against England

Australia became a nation on 1 January 1901 when 6 British colonies—New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania—united to form the Commonwealth of Australia. This process is known as Federation.

Reasons for Federation

For at least 60 000 years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have lived on these lands and practiced traditional cultures and languages. From the late 1700s, British colonies were established. By the late 1800s, these colonies had their own parliaments but were still subject to the law-making power of the British Parliament.

The colonies were almost like 6 separate countries; for example, each had its own government and laws, its own defence force, issued its own stamps and collected tariffs – taxes – on goods that crossed its borders. The colonies had even built railways using different gauges, which complicated the transport of people and goods across the continent.

By the 1880s the inefficiency of this system, a growing unity among colonists and a belief that a national government was needed to deal with issues such as trade, defence and immigration saw popular support for Federation grow. Sir Robert Garran, who was active in the Federation movement, later reflected that the colonies were united by a combination of 'fear, national sentiment and self-interest'.

Free trade

While tariffs provided the colonial governments with much revenue, they restricted trade and movement between the colonies. Tariffs increased the cost of goods and made it hard for manufacturers based outside a colony to compete with local producers.

Trade restrictions also made travelling between colonies difficult; the train journey between Melbourne and Sydney was delayed at the border in Albury while customs officials searched passengers' luggage. Free traders were among the most vocal supporters of Federation. They argued abolishing tariffs and creating a single market would strengthen the economy of each colony.

Defence

Prior to Federation, the colonies were ill-equipped to defend themselves. Each colony had its own militia consisting of a small permanent force and volunteers, but they all relied on the British navy to periodically patrol the Australian coastline. People feared the colonies could be vulnerable to attack from other nations with larger populations and military forces.

The colonies thought a united defence force could better protect Australia. This argument was strengthened by a report released in 1889 by British Major-General Sir J. Bevan Edwards. He found the colonies did not have enough soldiers, weapons or ammunition to adequately defend themselves. The report recommended a national defence force be established.

Immigration

In the late 19th century many people did not support immigration from non-British countries.

There was a concern 'cheap' non-white labour would compete with colonists for jobs, leading to lower wages and a lower standard of living. These anxieties stemmed partly from anti-Chinese sentiment dating back to the gold-fields of the 1850s. They also reflected resentment towards Pacific Islanders who worked in Queensland's sugar industry.

At the time, racial conflict was seen as a consequence of a multicultural society. It was felt a national government would be in a better position than the colonies to control immigration.

National pride

Colonists mostly shared a common language, culture and heritage, and increasingly began to identify as Australian rather than British. New South Wales Premier, Sir Henry Parkes, referred to this as 'the crimson thread of kinship that runs through us all'.

By Federation in 1901 over three-quarters of the population were Australian-born. Many people moved between the colonies to find work and sporting teams had begun to represent 'Australia'. In 1899 soldiers from the colonies who went to the Boer War in South Africa served together as Australians. Contemporary songs and poems celebrated Australia and Australians.

The Federation conventions

Convinced the colonies would be stronger if they united, Sir Henry Parkes gave a rousing address at Tenterfield, New South Wales in 1889 calling for 'a great national government for all Australians'. Parkes's call provided the momentum that led to Australia becoming a nation. Parkes knew popular support was not enough, so he lobbied his fellow premiers to back Federation.

On 6 February 1890 delegates from each of the colonial parliaments and the New Zealand Parliament met at the Australasian Federation Conference in Melbourne. The conference agreed 'the interests and prosperity of the Australian colonies would be served by an early union under the crown'. It called for a national convention—formal meeting—to draft a constitution for a Commonwealth of Australia.

1891 Federation convention

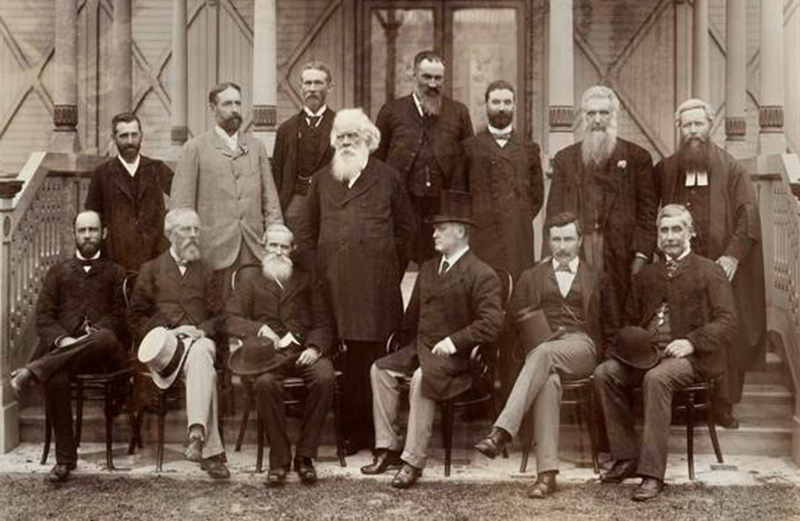

Members of the Australasian Federation Conference, 1890.

National Library of Australia, AN14292110

Description

A sepia-toned photograph of a group of men in formal attire in front of a building portico. Six men (including one wearing a top hat) are seated on chairs. Eight men stand behind. Henry Parkes is fourth from left and Alfred Deakin is sixth from left.

Copyright information

You may save or print this image for research and study. If you wish to use it for any other purposes, you must declare your Intention to Publish.

The first National Australasian Convention was held in Sydney in March and April 1891. It was attended by delegates from each of the colonies and the New Zealand Parliament. During the convention, Edmund Barton—who became the first Prime Minister of Australia—coined the catchcry 'a nation for a continent and a continent for a nation'.

The convention spent 5 weeks discussing and writing a draft constitution, which became the basis for the constitution we have today. Queensland Premier Sir Samuel Griffith is largely credited with drafting the constitution approved by the convention. However, his draft constitution was based on a version written by Tasmanian delegate Andrew Inglis Clark. Clark was inspired by the federal model of the United States, which, like Australia, faced the challenge of bringing together self-governing colonies as a nation.

Under the draft constitution the colonies would unite as separate states within the Commonwealth, with power shared between a federal – national – Parliament and state parliaments. This would give Australia a federal system of government.

Key features of the draft constitution included:

- A federal Parliament comprising the monarch (represented by the Governor-General), a Senate and a House of Representatives. The 2 houses would have similar law-making powers—laws could only be passed or changed with the approval of both houses.

- The federal Parliament would have responsibility for areas which affected the whole nation, such as trade, defence, immigration, postal and telegraphic services, marriage and divorce.

- The House of Representatives was to be elected based on population, with members representing electorates made up of approximately the same number of people. Each state would elect the same number of representatives to the Senate. This would ensure states with larger populations would not dominate the Parliament.

- A high court to interpret the constitution and resolve disputes between the federal and state governments.

- The power to make and manage federal law was to be divided between the Parliament (who would make the law), the Executive (who would implement the law) and the Judiciary (who would interpret the law).

The convention delegates took the draft constitution back to their colonial parliaments for consideration and approval. Faced with an economic depression, the parliaments lost enthusiasm for Federation. Federation's greatest champion, Parkes, retired from politics and following New South Wales governments did not share his passion for Federation.

The people's conventions

While the colonial parliaments put the issue of Federation to one side, it had fired the public's imagination. Groups such as the Australian Federation League in New South Wales and the Australian Natives Association in Victoria continued to push for Federation.

In 1893 a people's conference was held in Corowa, New South Wales, which agreed 'the best interests, present and future prosperity of the Australian colonies will be promoted by their early Federation'. The Corowa Conference agreed to a proposal from Victorian delegate John Quick, that:

- the colonial parliaments pass an Act to allow the direct election of delegates to a new Federation convention which would decide on a draft constitution

- a referendum be held asking the people to approve the draft constitution.

At a special premiers' conference held in Hobart in 1895 most of the colonies agreed to Quick's proposal. Queensland, fearing Federation might mean the loss of its Pacific Islander labour force, decided not to take part. By this stage, New Zealand had decided not to be part of the Federation process.

The following year the Bathurst Federation League, frustrated by the inaction of the colonial parliaments, held a second people's conference at which over 150 delegates renewed calls for a new Federation convention. Finally, in March 1896, elections for convention delegates were held in New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania and South Australia.

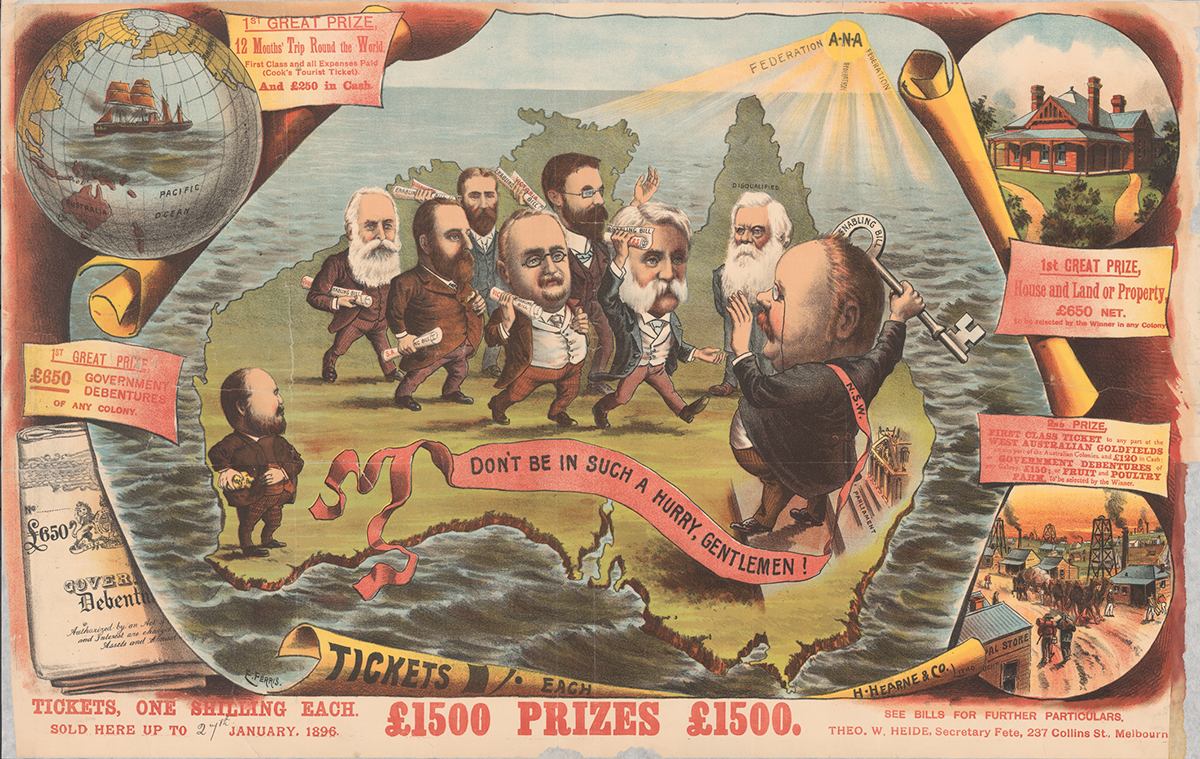

‘Don’t be in such a hurry gentlemen!’, 1896.

National Library of Australia, vn3582887

Description

A colour poster for a lottery with £1500 in prizes. Australia floats on an ocean and the ANA (Australian Natives Association) sun shines down. Six men each carrying a rolled-up piece of paper rush across the centre of the country towards New South Wales Premier Sire George Reid standing on the steps of the New South Wales Parliament House. Sir Henry Parkes looks on. In the South West of the country (where Perth is located) Western Australian Premier John Forrest looks on while putting a piece of gold in his pocket.

Copyright information

You may save or print this image for research and study. If you wish to use it for any other purposes, you must declare your Intention to Publish.

1897–98 Federation convention

The second National Australasian Convention met 3 times during 1897 and 1898 in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne, and used the 1891 draft constitution as a starting point for discussions. Elected and appointed representatives from all the colonies except Queensland took part in the convention.

One of the most significant changes made to the draft constitution related to the Senate. Senators would be directly elected by the people of each state instead of being selected by state parliaments. The new draft also set the number of members of the House of Representatives as roughly twice the number of senators.

Because the Senate and House of Representatives would have almost the same law-making powers, the delegates realised a way to break deadlocks between the 2 houses was needed. They decided disagreements could be resolved by dissolving – closing – both houses of Parliament and calling an election. The newly elected Parliament could then vote on the issue. If this failed to break the deadlock, it could be put to a vote in a joint sitting of both houses.

The convention also agreed to a proposal by Tasmanian Premier Sir Edward Braddon to return to the states three-quarters of the customs and excise tariffs collected by the federal government. 'Braddon's Blot', as it was called by its critics, was designed to reassure smaller states who were worried they would be worse-off under Federation.

On 16 March 1898 the convention agreed to the draft constitution. After being agreed by the colonial parliaments, the people of each of the 6 colonies were then asked to approve the constitution in referendums.

People involved in Federation

Many people around Australia were involved in Federation movement. Federal leagues, clubs and societies were formed from the 1890s to advocate for Federation. Press reports of the conventions were eagerly read and helped build popular support for Federation.

Many women were involved in the Federation movement. Women began their own Federal Leagues, in part to try and win the right to vote in the new nation. (Women had only won the right to vote in South Australia in 1894.)

Some of the major figures involved in the Federation movement were:

Sir Edmund Barton

- First prime minister of Australia.

- Supporter of Federation who coined the rallying cry ‘a nation for continent and a movement for a nation’.

Sir Samuel Griffith

- Premier of Queensland during the Federation process and the first Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia.

- Largely credited with writing the first draft of the Australian Constitution.

Sir Henry Parkes

- Premier of New South Wales.

- Gave the Tenterfield Oration that called for a united Australia and helped spark public support for Federation.

John Quick

- Delegate to the Federation conferences, including the Corowa People’s Conference where he proposed each colony send delegates to a conference to decide on a draft constitution.

Sir George Reid

- Premier of New South Wales during the Federation referendums.

- Known as ‘Yes/No Reid’ because although he criticised the draft constitution, he said he would vote ‘yes’ in the first referendum.

Catherine Helen Spence

- Was the only woman to stand for election to the second National Australasian Convention.

- Promoted a form of proportional representation, very similar to the system currently used to elect representatives to the Senate.

First referendum: 1898

In June 1898 referendums were held in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. Australia was the first nation to take a proposed constitution to the people for approval. (Switzerland had held a referendum to approve changes to its constitution in 1874).

Enthusiastic campaigns were waged urging people to vote 'yes' or 'no'. Anti-Federation groups argued Federation would weaken the colonial parliaments and interstate free trade would lead to lower wages and a loss of jobs. New South Wales Premier George Reid publicly criticised the proposed constitution but said he would vote for it in the referendum, earning him the nickname 'Yes-No Reid'.

The referendum was passed in Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania. Although a majority of voters in New South Wales voted 'yes' in the referendum, it did not attract the 80 000 'yes' votes set by the New South Wales colonial parliament as the minimum needed for it to agree to Federation. Queensland and Western Australia—concerned Federation would give New South Wales and Victoria an advantage over the less-powerful states—did not hold referendums.

'Secret' premiers' conference

In January 1899 the colonial premiers met privately to work out a way to bring about Federation. Western Australian Premier John Forrest did not attend.

In order to win the support of the New South Wales and Queensland colonial parliaments, the premiers made some further changes to the draft constitution. Among these was the decision to establish the Australian national capital within New South Wales at least 100 miles (160.9 km) from Sydney.

They also agreed the federal Parliament would only be required to return customs and excise tariffs to the states for the first 10 years of Federation.

Second 1899

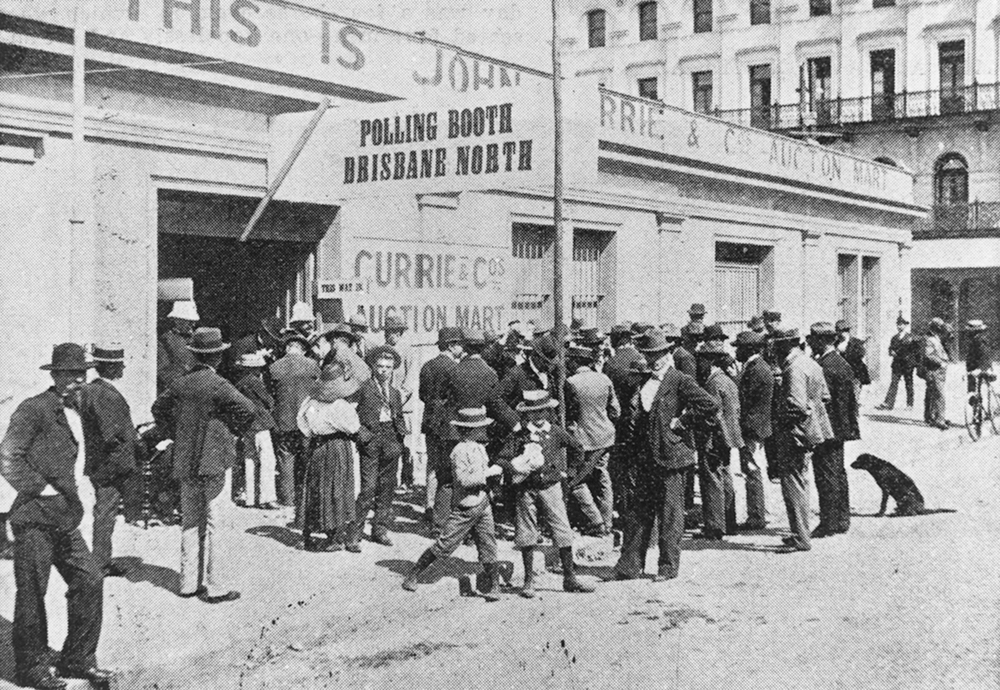

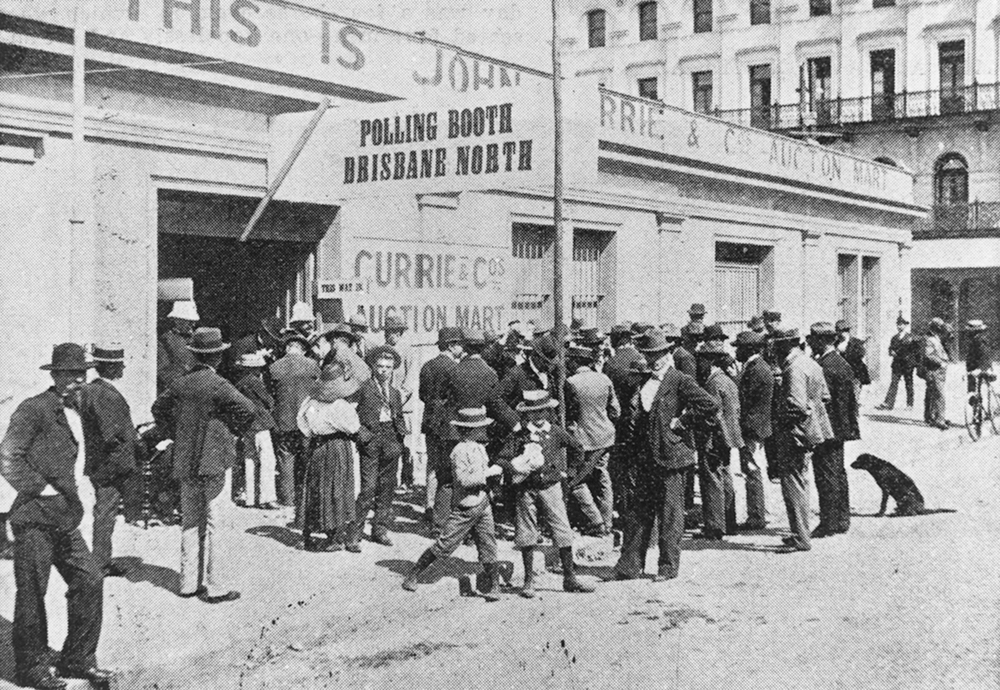

People line up outside a polling station on referendum day, Brisbane, 1899.

State Library of Queensland, Image No. 109589

People line up outside a polling station on referendum day, Brisbane, 1899.

State Library of Queensland, Image No. 109589

Description

A black and white photograph of a group of men, women and children (and a dog) gathered around the entrance of a low building. A sign reads 'Polling Booth Brisbane North'.

Between April and July 1899 referendums were again held in Victoria, South Australia, New South Wales and Tasmania. All 4 colonies agreed to the proposed constitution. Western Australia still refused to take part.

In September, Queenslanders agreed to the constitution by a narrow margin—just over 54 per cent of Queenslanders voted 'yes'. Queensland had waited to see whether New South Wales would federate before it held its referendum. The Brisbane Courier welcomed the result and urged all Queenslanders to now unite under 'The Coming Commonwealth':

Australia is born: The Australian nation is a fact … Now is accomplished the dream of a continent for a people and a people for a continent. No longer shall there exist those artificial barriers which have divided brother from brother. We are one people – with one destiny.

The Brisbane Courier, 4 September 1899.

Constitution Act

The constitution had to be agreed to by the British Parliament before Federation could proceed. In March 1900 a delegation—which included an observer from Western Australia and a representative from each of the other 5 colonies—travelled to London to present the constitution to the British Parliament.

The Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 was passed by the British Parliament on 5 July 1900. Queen Victoria signed the Act on 9 July 1900.

Western Australia joins the Federation

Three weeks after the Australian Constitution became law in Britain, a referendum was finally held in Western Australia.

Once it realised the other colonies would go ahead without it, the Western Australian colonial parliament reversed its opposition to Federation. Public opinion in Western Australia had also shifted. By 1900 there was widespread support for Federation, particularly among the large number of new settlers from the eastern Australian colonies who had moved to Western Australia as a result of the gold rush.

An overwhelming majority of voters agreed to federate, with double the number of 'yes' votes than 'no' votes.

Nationhood

Lord Hopetoun being sworn in as the Australian Governor-General, 1 January 1901.

Harold Bradley, National Library of Australia, an13117410-4

Lord Hopetoun being sworn in as the Australian Governor-General, 1 January 1901.

Harold Bradley, National Library of Australia, an13117410-4

Description

A sepia toned photograph looking into a rotunda. A group of men under the dome are gathered around a table. Women with large hats stand outside the rotunda watching the events taking place inside. Decorations hang from the dome.

Copyright information

You may save or print this image for research and study. If you wish to use it for any other purposes, you must declare your Intention to Publish.

The Commonwealth of Australia was declared on 1 January 1901 at a ceremony held in Centennial Park in Sydney. During the ceremony, the first Governor-General, Lord Hopetoun, was sworn-in and Australia's first Prime Minister, Edmund Barton, and federal ministers took the oath of office.

Many Australians welcomed nationhood. Up to 500 000 people lined the route of the Federation parade as it travelled from the Domain to Centennial Park and about 100 000 spectators witnessed the ceremony.

Across Australia people celebrated with parades, processions, school pageants, firework displays, sporting events, 'conversaziones' – discussion evenings – and special dinners. Elaborate Federation arches decorated main streets and buildings were lit up at night. In Sydney the celebrations continued for a week.

First Parliament

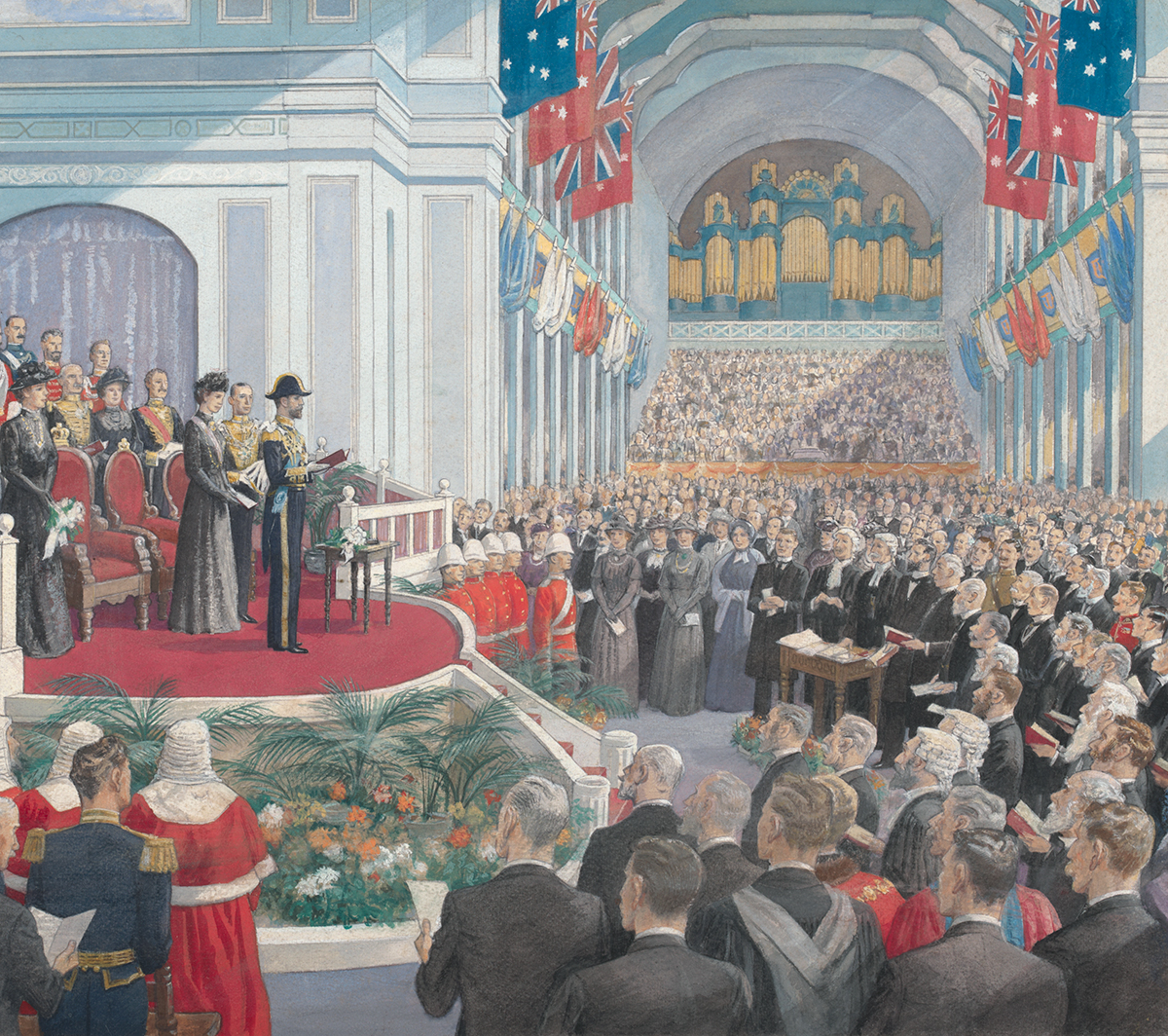

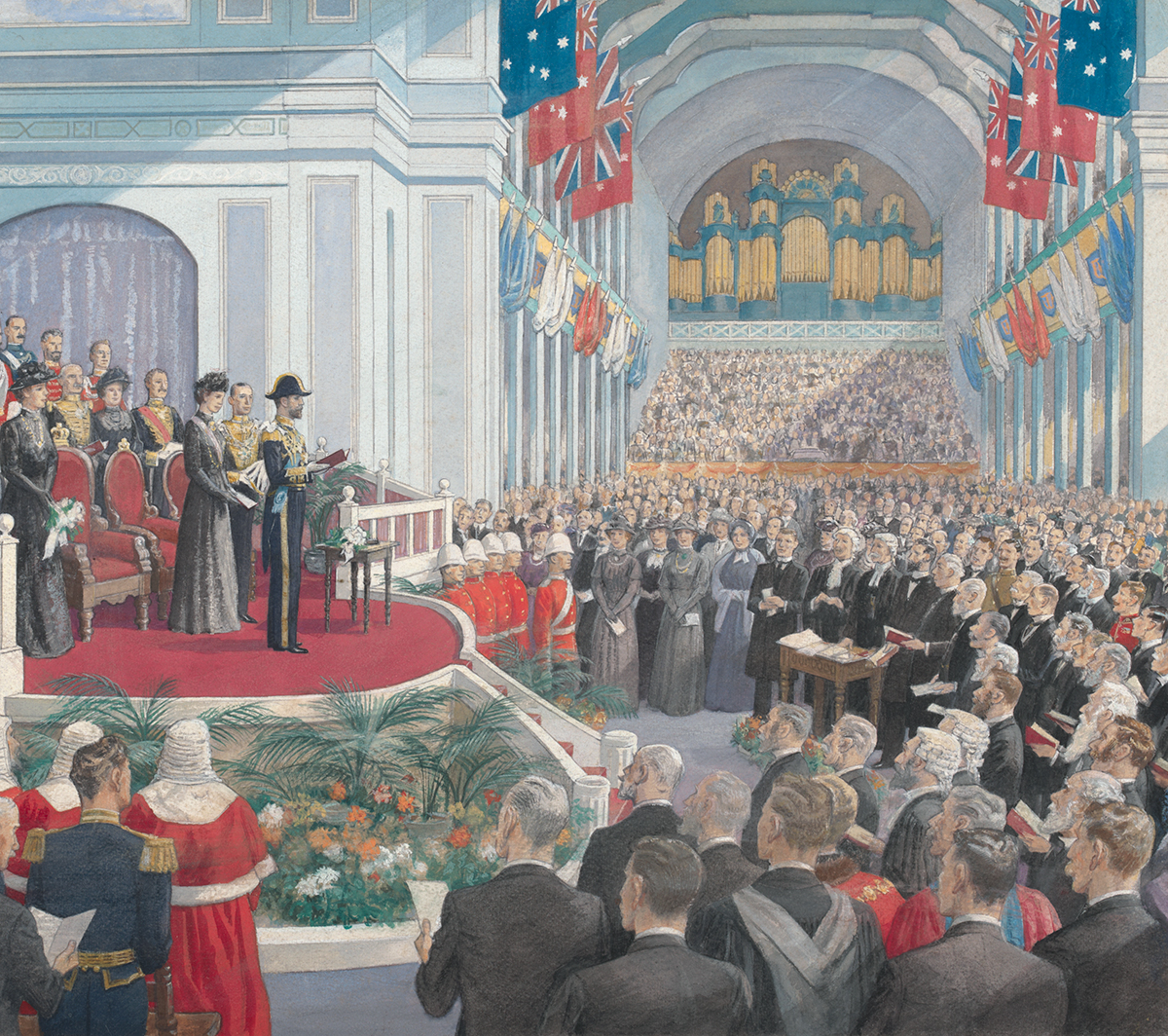

The Duke of Cornwall and York opens the first federal Parliament, 9 May 1901.

State Library of Victoria

The Duke of Cornwall and York opens the first federal Parliament, 9 May 1901.

State Library of Victoria

Description

This colour engraving shows the official opening of the of the first federal Parliament. The Duke of Cornwall and York, dressed in full military uniform, reads from a book. He and other dignitaries stand on a platform looking down on a great crowd. Judges, military personel, accademics, women and lawyers can be seen in the crowd. Flags are drapped from the mezzanine level of the Exhibition Building.

The first federal elections for the new Australian Parliament were held on 29 and 30 March 1901. Eighty-seven of the 111 newly elected parliamentarians had been members of colonial parliaments, including 14 who had been colonial premiers. Several had also participated in the drafting of the Constitution and were active in the push for Federation – 10 had been at the 1891 National Australasian Convention and 25 attended the second National Australasian Convention.

The first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia was opened at noon on 9 May 1901 by the Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V). The lavish ceremony took place in the Exhibition Building, Melbourne, and was attended by over 12 000 guests.

In his address, the Duke told the gathering:

It is His Majesty's [King Edward VII] earnest prayer that this union so happily achieved may, under God's blessing, prove an instrument for still further promoting the welfare and advancement of his subjects in Australia and for the strengthening and consolidation of his Empire.

Members of parliament were sworn-in by the Governor-General and then travelled by foot and horse-drawn carriage to Victoria's Parliament House. The Senate then met at 1.10pm in the Legislative Council and the House of Representatives met at 2.30pm in the Legislative Assembly for the first session of federal Parliament. The Victorian Parliament House remained the temporary home of federal Parliament until 1927, when a new Parliament House was opened in Canberra. During this time, the Victorian Parliament met in the Exhibition Building.

In Melbourne the opening of Parliament was marked by 2 weeks of celebrations. The enthusiasm with which Australians greeted Federation and the first federal Parliament demonstrated the nation was eager to unite as 'one people'.

Federation timeline

| 1889 | Sir Henry Parkes, Premier of New South Wales, urges the colonies to federate. |

|---|---|

| 1890 | The Australasian Federation Conference recommends a national convention be held to draft a constitution for a Commonwealth of Australia. |

| 1891 | The first National Australasian Convention is held in Sydney and drafts a constitution. |

| 1891–1894 | Economic depression means the colonial parliaments lose interest in Federation. |

| 1893 | A people's conference in Corowa, New South Wales, urges the colonial parliaments to hold a new convention to decide on a draft constitution. |

| 1896 | A second people's conference in Bathurst, New South Wales, renews calls for another Federation convention. |

| 1897–1898 | The second National Australasian Convention meets in Adelaide, Sydney and Melbourne, and agrees to the constitution. |

| 1898 | Referendums are held in New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia and Tasmania to approve the constitution. It is agreed to by all but New South Wales. |

| 1899 | In January a secret premiers' meeting agrees to several changes to the constitution. Between April and July referendums are held in South Australia, New South Wales, Victoria and Tasmania at which a majority vote 'yes' to the bill. In September Queensland voters agree to the constitution. |

| 1900 | In March a delegation travels to London to present the constitution to the British Parliament. On 5 July the British Parliament passes the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. On 9 July Queen Victoria signs the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900. On 31 July Western Australia holds a referendum at which an overwhelming majority of voters approve the Constitution. |

| 1901 | On 1 January the Commonwealth of Australia is proclaimed in Centennial Park, Sydney. On 29 and 30 March the first federal election is held. On 9 May the Duke of Cornwall and York (later King George V) opens the first Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia in the Exhibition Building in Melbourne. |

Results of the referendums on the draft bill to constitute the Commonwealth of Australia

1898

While a majority of voters in each colony voted 'yes', the referendum in New South Wales did not attract the 80 000 votes set by the New South Wales colonial parliament as the minimum needed for it to agree to Federation. Queensland and Western Australia did not hold referendums.

| YES | NO | |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 71 595 | 66 228 |

| South Australia | 35 800 | 17 320 |

| Tasmania | 11 797 | 2716 |

| Victoria | 100 520 | 22 099 |

| Total | 219 712 | 108 363 |

1899

Majorities were achieved in all colonies.

| YES | NO | |

|---|---|---|

| New South Wales | 107 420 | 82 741 |

| Queensland | 38 488 | 30 996 |

| South Australia | 65 990 | 17 053 |

| Tasmania | 13 437 | 791 |

| Victoria | 152 653 | 9805 |

| Total | 377 988 | 141 386 |

1900

Result of the referendum held in Western Australia on 31 July 1900.

| YES | NO | |

|---|---|---|

| Western Australia | 44 800 | 19 691 |